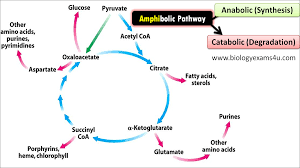

An amphibolic route is a metabolic system that can both create complex compounds from simpler ones and break down molecules to release energy. It involves both catabolic and anabolic events. An excellent illustration of an amphibolic route is the Krebs cycle, sometimes referred to as the citric acid cycle.

Explanation: Energy is released during the breakdown of big molecules into smaller ones, a process known as catabolism. Consider it analogous to tearing down a structure for scrap. Energy is needed for anabolism, which is the process of creating complex molecules from simpler ones. Consider it as building something new out of the scrap. Amphibole pathways are capable of both.

In addition to using the byproducts of those breakdowns to create new molecules, they are able to break down molecules to liberate energy.

Energy is needed for anabolism, which is the process of creating complex molecules from simpler ones. Consider it as building something new out of the scrap. Amphibole pathways are capable of both. In addition to using the byproducts of those breakdowns to create new molecules, they are able to break down molecules to liberate energy.

Oxaloacetate: Oxaloacetate is essential to the respiration of cells. In order to release energy in the form of ATP, NADH, and FADH2, it oxidizes molecules such as acetyl-CoA, which is produced during the breakdown of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. Importantly, it also supplies building blocks for amino acids and other bimolecular, such as oxaloacetate and α-ketoglutarate. Important distinctions between amphibole and alternative pathways:

Purely Catabolic: These processes (like glycol sis) only degrade molecules.

Important characteristics of amphibolic pathways

They serve two purposes: they promote anabolism, which is the synthesis of complex molecules from simpler ones, and catabolism, which is the breakdown of complex molecules to liberate energy.

1. Energy generation: They play a catabolic role in the synthesis of ATP.

2. Supply of precursors: They offer intermediates that are useful in a number of anabolic (biosynthetic) pathways.

Amphibolic pathway examples

This dual character is evident in a number of important metabolic pathways:

Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle: This is regarded as the quintessential illustration of an amphibolic route.

Catabolic function: releases energy by oxidizing acetyl-CoA, which is taken from proteins, lipids, and carbs, to create ATP, NADH, and FADH2.

Anabolic function: Amino acids, nucleotides, and other significant biomolecules can be synthesized via intermediates like oxaloacetate and α-ketoglutarate.

Glycolysis has an anabolic function in addition to its catabolic one, which involves breaking down glucose to produce energy for energy production.

For instance, glycerol can be produced for fat synthesis from (DHAP), an intermediate of glycolysis.

Phosphate Pentose Pathway (PPP): Pentose sugars, which are substrates for nucleotide synthesis, and NADPH, a reducing agent necessary for biosynthesis, are produced by this process.

For what reason are amphibolic pathways necessary?

- Amphibolic pathways are essential for cell function because they: Link anabolic and catabolic processes to allow cells to manage energy and resources effectively. Allow for flexibility in the breakdown and synthesis of molecules to aid in adaptability to various dietary situations.

- Assist cellular growth and repair by ensuring a coordinated supply of precursors for different biosynthetic processes. Amphibolic pathways essentially show how metabolic processes within living things are interconnected and efficient, enabling them to react to their internal and external environments in an efficient manner.

Kreb’s Cycle

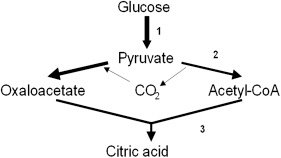

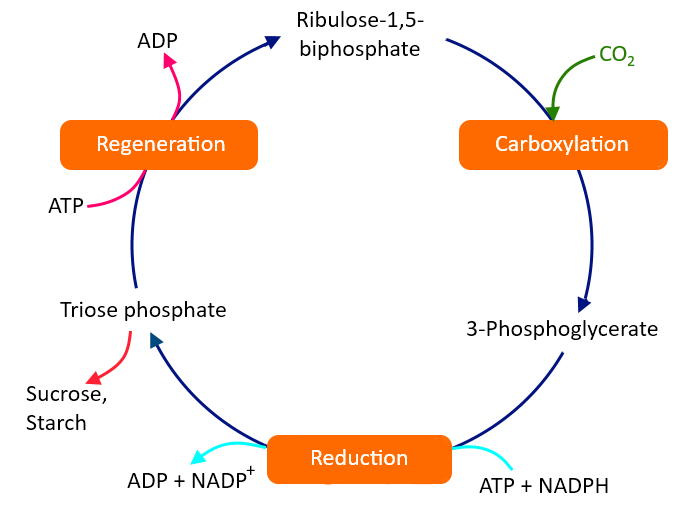

The central driver of cellular respiration is the citric acid cycle, or the tricarboxylic acid or Krebs’ cycle. This cycle is considered the main source of energy for cells, and it is also a necessary part of aerobic respiration. Acetyl-CoA, which is derived from glucose and produced by the oxidation of pyruvate, is taken as the starting material, and when it is there in the series of redox reactions, most of its bond energy is harvested in the form of NADH and FADH₂, and ATP molecules. NADH and FADH₂ are generated in the TCA cycle and are the reduced electron carriers, pass their electrons through oxidative phosphorylation into the electron transport chain, and most of the ATP that is produced in cellular respiration will be generated.

Process of Kreb’s Cycle

Kreb’s cycle in the case of eukaryotes takes place in the matrix of the mitochondria, which is similar to the conversion of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, while in the case of prokaryotes, all these processes take place in the cytoplasm. Kreb’s cycle, as the name suggests, is a closed-loop in which the molecule used in the first step is again reformed by the last part of the pathway.

- Acetyl-CoA is combined with oxaloacetate, which is a 4-carbon acceptor molecule, in the first step, in order to form citrate, which is a 6-carbon molecule.

- Then, two carbons are released from citrate, a 6-carbon molecule, as carbon dioxide molecules, producing an NADH molecule each time in a similar pair of reactions.

- The key regulators of the Krebs’ cycle are the enzymes that catalyze these reactions. These enzymes speed up or slow down the reactions on the basis of the energy needs of the cell.

- Then, the remaining 4 molecules of citrate undergo a series of additional reactions. An ATP molecule is made first or a similar molecule, GTP, in some cells. Then the electron carrier FAD is reduced to FADH₂. Then, finally, another NADH is generated.

- In this set of reactions, the starting molecule, oxaloacetate, is regenerated in order for the repetition of the cycle.

- In a single turn of the Krebs’ Cycle, molecules of carbon dioxide are released, producing 3 NADH, one FADH₂, and one ATP or GTP.

- Since there are two pyruvates, the Krebs’ cycle goes around twice for each molecule of glucose that has entered the cellular respiration, and hence two acetyl-CoAs are made per glucose.